- Home

- Lynne Reid Banks

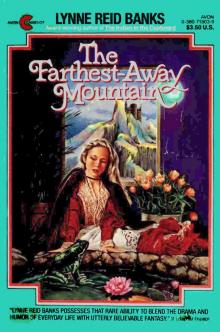

The Farthest-Away Mountain

The Farthest-Away Mountain Read online

For Dee McKenna

who promotes reading

in the farthest-away

place in my world.

Table of Contents

A Preface

1 The Call

2 The Wicked Wood

3 The Cabin in the Meadow

4 Drackamag

5 The Spikes

6 The Mountain Path

7 The Gargoyles

8 The Tunnel

9 The Painted Snow

10 Graw

11 Croak Again

12 Up the Mountain

13 The Blue Bead

14 Another Poem

15 The Witch

16 The Story of the Mountain

17 The Witch Ball

18 Doom

19 Trolls

20 Changes

21 Home

22 The Ring

23 The Palace

24 Rally

25 Gog

26 Back to the Mountain

A Preface

Once upon a time, in a little village that lay in a mountain valley, there lived with her family a girl called Dakin.

Her country was beautiful. The air there was so clear that it sparkled in the sunshine as if it were made of diamond dust. Every morning, winter or summer, Dakin could look out of her bedroom window and see the farthest-away mountain, its black peak standing up clear of the thick shawl of pine-woods it wore on its lower slopes. Between the peak and the woods was a narrower shawl of snow. This snow changed color in a most odd way. Sometimes it was a sharp blue, and sometimes purple, or pink, or even yellow, or green. Dakin would watch this snow in great puzzlement, for snow, after all, is supposed to be white.

She looked at the pinewoods, too. Forests always gave Dakin a shivery feeling, half unease and half excitement. There was no knowing what lay beneath those close-together branches, and no one could tell her, because no one in the town—not even her father, who had visited the city and the ocean—had ever been to the farthest-away mountain.

Old Deegle, the ballad singer and storyteller who came once a year to bring them news and tales from all over the country, said that the reason no one had ever been to the farthest-away mountain was because however long you traveled toward it, it always stayed in the distance. This, he said, was due to a spell that had been placed on it by a magician from their very own village whose wicked son had disappeared into the mountain long, long ago.

But now that you know as much as anyone then knew about the farthest-away mountain, I must tell you about Dakin. She is the most important person in the story.

Dakin was small and dainty and wore full skirts to her ankles over lots of petticoats, but no shoes except when it was very cold, and then she wore lace-up boots. She had long hair, so fair as to be almost white. She was supposed to keep it in plaits, but usually she didn’t, and it blew out behind her and got tangled; then her mother would have to brush and comb it for hours to get all the knots out. She had a turned-up nose and eyes the color of the blue mountain flowers that grew in spring, and small brown hands and feet. She was fourteen.

In those days a girl was quite old enough to get married by that age. Dakin was the prettiest girl in the village; she could sing like a thrush and dance like a leaf in the wind, and besides, she was a marvelous cook. So that, until you know certain other things about her, it’s difficult to understand why her parents were so very anxious about her chances of getting married.

It had begun four years earlier, when she was ten, and had announced to her mother and father and two sisters and two brothers that she was not going to marry until she had seen some of the things she wanted to see, and done some of the things she wanted to do. She went on to tell them that there were three main things, which were these: she wanted to visit the farthest-away mountain; she wanted to meet a gargoyle; and she wanted to find a prince for her husband.

The family was at supper at the time. Her father and mother had looked at each other, and so had her brothers and sisters. Then they all looked at Dakin, who was calmly drinking her soup.

“But Dakin, you can’t go to the farthest-away mountain,” said her father. “No one’s ever been there, not even me, and I’m the most traveled man in the village.”

“Dakin, what do you want to see a gargoyle for?” scolded her mother. “If you ever saw one, you’d be so frightened you’d turn into stone.”

“You’re a silly goose,” said her elder brother, Dawsy.

Dakin had stopped drinking her soup and was looking out of the window toward the farthest-away mountain, which in the clear air looked as if it were just beyond the end of the village. “I must go to the farthest-away mountain and see what’s in the forest,” she said. “And I want to find out what makes the snow change color.”

“There’s nothing in the forest that you won’t find in our own pinewood,” argued Margie, her second brother, who thought he knew everything. “And I can tell you why the snow changes color, without you going to see: it’s the sun shining on it.”

“Shining blue? Shining green?” said Dakin scornfully.

“The gargoyle part’s silly, though,” said her littlest sister Triska, who was only six. “I’ve seen pictures of them in Pastor’s book of church pictures, and they’re horrid and ugly.”

“I think they look sad, ” said Dakin. “I want to find one and ask why gargoyles look sad.”

“They’re only statues of heads. They can’t talk!” scoffed Sheggie with her mouth full. “Anyway,” she added with some satisfaction, “you’ll have to give in about the prince. There’s only Prince Rally, and he can’t marry anyone until the Ring of Kings is found.”

“Which might be any time,” said Dakin.

“Which will be never,” said Margie. “It’s been missing for seventeen years, since it was stolen by a troll at Prince Rally’s christening. And no one in the royal family can get married without it.”

“Besides,” said Sheggie, “what makes you think he’d marry you? He’d want to marry a princess.”

But a dreamy look came into her eyes, so that Dawsy, who was a tease, said, “Look at Sheggie, wishing he’d come and ask her!” And they all laughed.

Dakin’s brothers and sisters forgot what she’d said, and her father and mother hoped Dakin had forgotten, too. Four years went by, and young men began to ask for her hand in marriage. But when her father would tell her that this one or that one had asked for her, Dakin would only shake her head. “It’s no good, Father,” she would say. “I’ve made up my mind to visit the farthest-away mountain, and see a gargoyle, and find a prince to be my husband.”

Her father at first tried to reason with her, and later he got angry and shouted, and as time went by he grew pathetic and pleaded, which was hardest of all for Dakin, who loved him, to resist. But her mind was made up and somehow she couldn’t change it.

So now she was nearly fifteen and there was hardly a young man in the village who had not asked for her at least once and gone away disappointed. Sheggie and Dawsy and Margie were all married, so that left only Triska at home to keep her company. But she seemed quite happy and usually sang as she did her work around the house; only sometimes, on her way past a window or across the grass outside the back door, she would stop with a dishcloth or a plate of chicken meal in her hands and look to the left, along the valley to where the royal estates lay, with the spires, high walls, and shining golden gates of the palace.

Then she would turn and look the other way, toward the mountain. She would stand quite still, as if listening; then she would sigh very deeply before moving on again.

1

∞ ∞ ∞ ∞

The Call

One morning, very early, Dakin woke up sharp

ly to find herself sitting up in bed.

“Somebody called me!” she thought. “I heard a voice in my sleep!”

She jumped up and ran to the open window in her long nightgown. Outside the sun was just appearing beyond the farthest-away mountain, breathing orange fire onto the strange, patchwork snow and streaking the pale sky with morning cloud colors. It was still cold, and Dakin shivered as she called softly into the empty world:

“Did somebody want me?”

No one answered, and Dakin thought she must have dreamed it. But just as she was turning to jump back into bed again, she saw something which nearly made her fall out of the window.

The mountain nodded.

At least, that’s what it looked like. As the sun almost burst over the top, the black head of the mountain seemed to dip, as if to say, “Yes, somebody wants you.”

Dakin stared and stared, forgetting the cold, until the sun was completely clear of the peak and stood out by itself, round and red and dazzling. Nothing else happened, but all the same, Dakin knew. It was time to start.

Moving quickly and quietly, she put on her warmest dress with three red petticoats under it, her stout climbing boots which laced with colored lacings up past her ankles, and the white apron she always wore. She hadn’t time to plait her hair, so she pushed it out of the way under her long white stocking cap. Then she tiptoed downstairs.

It was difficult to be quiet because of the boots, which she should have left off till later. Her mother called from her bedroom:

“Dakin, is that you?”

“Yes, Mother,” said Dakin, wondering how she would explain her going-out clothes if her mother saw her.

“Put on the water for the porridge, little one,” called her mother sleepily.

Dakin almost changed her mind about going at that moment. She wanted to run into her parents’ room and curl up under the big feather quilt, hugging her mother’s feet as she used to when she was little. It would be so safe and happy to put the water on the big black stove for the porridge, and later to eat it with coffee and wheaty bread with Mother and Father and Triska, and feed the hens and do the washing and go on all day as if the farthest-away mountain had never called her.

For a moment she paused on the stairs. Then she thought, “No. I must do what I’ve said I’ll do.”

So she went on downstairs, and pumped the water very quickly, and put it on to heat. Then she hastily filled her knapsack with the things she thought she’d need—a chunk of bread and another of cheese, a slab of her mother’s toffee, a mug and a knife, a candle and some matches. Then she looked around. On the window ledge was a book of poems her father had brought back for her from the city, and she put that in.

Then, as an afterthought, she lifted off the mantelpiece the little brass figure of a troll that her father had found years and years ago on the very edge of the pinewood. She held the little man in her hand and looked at his impish, bearded face under the pointed hat.

“I shouldn’t take you really,” she whispered. “You’re brass and you’re heavy.”

But nonetheless she slipped him into her knapsack and felt him slide between the loaf and the book and lie at the bottom. And she didn’t feel so lonely suddenly.

Now she could definitely hear sounds of movement from above, and she knew that soon they’d be coming. So she pulled her warm brown cloak down from the hook behind the back door and wrapped it around her; then she put all her weight on the heavy latch, and the next moment she was out in the bright morning, running, running toward the farthest-away mountain with her white stocking cap flying out behind her and her knapsack bumping.

First she had to go through the village, or rather across a corner of it. People she knew were just opening up their shutters and putting their bolsters and quilts on the upstairs window ledges to air.

“Good morning, Dakin!” they cried as she passed. “Where are you off to in such a hurry?”

“I’m going to the farthest-away mountain,” she called back over her shoulder. But they all thought she was joking, and laughed, and let her go.

2

∞ ∞ ∞ ∞

The Wicked Wood

Soon she had left the village behind. She climbed a little green hill and ran down the other side, and when she looked back she couldn’t see any of the village except the tip of the church steeple. She crossed a rushing, mint-green river by jumping from rock to rock, and then she was as far away from home as she’d ever been. The children of the town were never allowed to go beyond the river alone, because beyond the river was the wood, and the wood could be dangerous, even in daytime. Under the thick pine branches it was always like dusk, and every direction looked the same, so that it wasn’t just easy to get lost, it was almost impossible not to.

Dakin paused on the dark edge of the wood and looked back over the sunny-smooth meadows with their knuckles of rock and gay foaming river dashing on its way to the sea. She looked ahead, but being under the first branches she couldn’t see the farthest-away mountain any more, only the murky depths of the forest, its tree trunks filling in the spaces between each other until there seemed to be a solid wall of them.”How will I know that I’m going straight toward the farthest-away mountain, and not walking in circles like Megers Hawmak when he went in after his cow and was lost for three days?” she wondered.

“Better go back,” whispered a little voice inside her head, “before it’s too late.”

Dakin took a step back toward the rushing river, and then stopped.

“No,” she said aloud, and started off under the trees.

Before she’d been walking for three minutes everything around her grew dim and every direction looked the same. She turned to look back the way she had come, but it was just as closed in behind as ahead, with only little trickles of sunshine penetrating the thick pine needles. When she turned to go on she found she didn’t know whether she’d turned in a half circle or a whole circle, whether she was going back toward the village or on toward the mountain, or in another direction altogether. There were no friendly sounds of birds or scurryings of little animals, no sounds when she walked on the spongy needles and moss, no hum of insects or whisper of breeze—in fact, no sounds anywhere at all.

“I’m frightened!” realized Dakin. It was for the first time in all her life, and it was a horrible feeling.

She had never felt so completely alone. She felt tears pricking her eyes like pine needles. And then she remembered.

She wasn’t quite alone, after all. She had the little troll.

Quickly she slipped out of the straps of her knapsack, opened it, and reached to the bottom between the rough loaf and the smooth book. Her fingers touched the small, heavy figure, and closed around it. It fitted her hand in a comforting way. She drew the little man out and looked at him. He reminded her of home and the warm kitchen. A tear fell off her cheek and splashed on his long brass goblin’s nose.

He sneezed.

Dakin shrieked and dropped him in the moss. She backed against a tree, her eyes huge and her hands to her face.

The little troll picked himself up. He stood knee-deep in moss with his hands on his hips, looking up at her. For a long moment they stared at each other. Then the little man, in a voice like the faraway cracking of twigs, said:

“Could I borrow your handkerchief, madam?”

Without speaking, Dakin took it out of the pocket of her apron and gingerly held it out to him as if expecting him to bite her. He reached up his tiny hand and, holding the handkerchief by one corner with most of it on the ground, he wiped her tear off his face and carefully dried his beard.

“Thank you,” he said politely. “I’m quite tarnished enough,” he added. “Moisture doesn’t do brass any good, you know.” He sounded a little bit severe about it.

Dakin went down on her knees beside him, staring at him, quite unable to believe it.

“Would you mind explaining,” she said shakily, “how you come to be alive?”

“Certainl

y,” replied the little figure. “Only would you please pick me up? I’m getting a bit tired of shouting.”

Cautiously she laid her hand palm upward on the moss beside him, and he stepped briskly onto it, holding onto her thumb to steady himself as she got carefully to her feet. She looked at him in bewilderment. Of course, it was darkish and difficult to be sure, but he seemed just the same—that is, he hadn’t turned into a flesh-and-blood little man. He was still heavy for his size, and he still seemed to be made of brass. Only now he was definitely and undoubtedly alive. He wore leggings and pointed-toed boots, and a jacket belted with a smooth belt without a buckle. He was rubbing at his sleeves to try to get the tarnish off them, and gradually the metal was becoming brighter.

“That’s better!” said the troll.

“We did our best,” said Dakin, “but we couldn’t get into the cracks.”

“Quite. Quite,” said the troll. “I’ll soon have it all off. Now we must talk. By the way, where are you going?”

“To the farthest-away mountain,” said Dakin.

The little man was so startled he had to grab her thumb with both hands to save himself from toppling to the ground.

“You don’t mean—not to the—f-f-f-farthest-away mountain?” he whispered in a trembling voice.

“Why not?” asked Dakin.

“But you can’t! No one’s ever been there! It’s inhabited by gargoyles—”

“Gargoyles?” cried Dakin excitedly.

“Yes. And ogres and monsters and witches and—”

“If no one’s ever been there, how do you know?” asked Dakin.

The troll clapped his hand to his mouth, as if he had said too much.

“Well, I—I don’t really know, that is, I’ve—” he stammered.

“You’ve been there! You have!” cried Dakin.

“Well—”

“Haven’t you?”

“Well, as a matter of fact—I have. In fact I used to live there. Once. Years and years and years ago. And I don’t want to go back!” he added. “So you’d better go straight home like a sensible girl, and put me back on the mantelpiece where it’s safe.”

Two Is Lonely

Two Is Lonely Uprooted - a Canadian War Story

Uprooted - a Canadian War Story The Backward Shadow

The Backward Shadow Harry the Poisonous Centipede: A Story to Make You Squirm

Harry the Poisonous Centipede: A Story to Make You Squirm The Secret of the Indian (The Indian in the Cupboard)

The Secret of the Indian (The Indian in the Cupboard) The L-Shaped Room

The L-Shaped Room The Mystery of the Cupboard

The Mystery of the Cupboard The Farthest-Away Mountain

The Farthest-Away Mountain Harry the Poisonous Centipede Goes to Sea

Harry the Poisonous Centipede Goes to Sea The Fairy Rebel

The Fairy Rebel Harry the Poisonous Centipede's Big Adventure: Another Story to Make You Squirm

Harry the Poisonous Centipede's Big Adventure: Another Story to Make You Squirm The Indian in the Cupboard

The Indian in the Cupboard The Return of the Indian

The Return of the Indian I, Houdini

I, Houdini The Key to the Indian

The Key to the Indian The Warning Bell

The Warning Bell Alice by Accident

Alice by Accident Uprooted

Uprooted Writing On the Wall

Writing On the Wall The Adventures of King Midas (Red Storybook)

The Adventures of King Midas (Red Storybook) Harry the Poisonous Centipede's Big Adventure

Harry the Poisonous Centipede's Big Adventure Harry the Poisonous Centipede

Harry the Poisonous Centipede The Dungeon

The Dungeon Bad Cat, Good Cat

Bad Cat, Good Cat The Indian in the Cupboard (Essential Modern Classics, Book 1)

The Indian in the Cupboard (Essential Modern Classics, Book 1) Tiger, Tiger

Tiger, Tiger