- Home

- Lynne Reid Banks

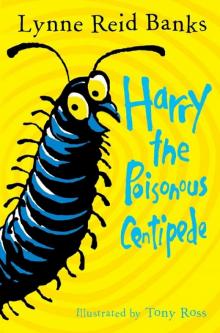

Harry the Poisonous Centipede's Big Adventure Page 5

Harry the Poisonous Centipede's Big Adventure Read online

Page 5

After a long crawl, they found themselves once again among palm trees. The ground under them was firm and diggable, if they needed to dig. They wanted to. They wanted to make themselves a tunnel and crawl into it and never come out again, to face all the dangers and hardships they’d found out about. But there was something they wanted more.

“Grndd. Stop a bit.”

George stopped.

“Where are we going?”

“Where do you think?”

“Home?”

“Of course.”

If a centipede could be homesick – wait a minute, what am I talking about? Of course centipedes can be homesick. Most creatures can. They crouched down, every little segment filled with longing.

“I want my mama,” crackled Harry very softly.

George said nothing. He wanted her, too.

“But how can we find our way back?”

George still said nothing. It was a terrible question. He hadn’t the slightest notion of the answer.

“Let’s think.”

They thought. George said, “How far do you think the giant flying-swooper carried us?”

“I don’t know. It seemed to last for ever.”

“No it didn’t. I was looking down through the hard-air. We went over a bunch of trees. Then it was the no-end-puddle, only I didn’t know what it was then.”

Harry looked up. “Mama knows about the no-end-puddle. She might even have seen it, or how could she tell us stories about it? Maybe we’re not so far from home.”

“But how can we find it?”

Harry said slowly, “It’s got a smell all of its own.”

George realised this was true. When they’d been out exploring the no-top-world, they always knew how to find their way back – as long as they didn’t stray too far from their home-tunnel.

“Put your feelers up. See if you can sense it.”

They ran here and there, sensing and smelling with all their might. But they didn’t get even a whiff of the dear, familiar scent.

“It’s no good. We’re too far from it.”

“So what can we do?”

“We’ll just have to march away from the no-end-puddle. Then maybe we can—” But Harry didn’t know how to go on. He had no idea what they could do. He thought of them wandering about for the rest of their lives, looking for home, looking for Belinda. Facing dangers, being hungry, being frightened and lonely. Maybe never, ever finding what they were looking for.

It was such a terrible thought, he didn’t want even to start. He felt all his hope and his energy draining out of him, like water out of his breathing holes that time he was washed ashore upside down.

But George wouldn’t let him give up.

“Oh, come on, Hx! Remember your dad, what a brave centipede he was! He’d be so proud of you if he knew what you’ve come through already. I wouldn’t give up if I had a dad like that, a-centipede-that-tackled-a-Hoo-Min!”

Slowly Harry pressed down on his forty-two feet and lifted his body.

“Right, Grndd. You’re right. Let’s get started.”

16. The Worst Things

in the World

They crawled and ran and rested and crawled more until dawn broke. And something else broke, too. No, it wasn’t their backs – aching and weary as they were from their long march. It was the weather.

Where the centipedes lived, there weren’t four seasons, as most of us have. There were just two – the rainy and the dry.

For all of Harry’s and George’s short lives, it had been dry. And hot. Very hot. But while they’d been marching through the night, there’d been a change. The sky had become heavy with clouds. They didn’t know this, but they did feel the change in the air. And they heard rumbles of distant thunder. These had made the two centis crouch down in fear, but apart from a cool, damp breeze (which was pleasant), nothing had happened.

Now, quite suddenly, it did.

A big splosh of water fell on George. He stopped short, shook himself, looked around crossly, and then started forward again, though his legs would hardly hold him for tiredness.

Next, another big splosh – this time right on Harry’s head.

If centipedes could sneeze, he would have sneezed.

“What’s going on?” they both said at once. Because now there were sploshes all around them, sending up little fountains of dust as they hit the dry ground. They looked around anxiously. Had the no-end-puddle somehow flown after them? Was it out to get them, drop by drop?

But the water wasn’t salty. And suddenly Harry knew what it was.

“It’s the great-dropping damp!” he crackled excitedly. “Mama told me about it! She says big-yellow-ball sends it when he gets fed up with shining! She said when it comes you have to go underground or it can wash you away!”

By that time they were nearly exhausted. Their legs would hardly hold them up, their cuticles felt like a coating of stone, their feelers drooped, and they were too hungry to feel hungry any more. But the rain was now falling in torrents and they had to do something quickly.

Harry led the way up a slope. “Mama said if I was ever caught in the great-dropping-damp I should get under something and find a tunnel!” he said importantly. George, blowing rain out of his breathing-holes, followed silently.

They struggled through the heavy sploshing drops that were now falling all around them and on top of them. They were in luck. At the top of a slight rise was a jutting rock that made shelter from the rain. Underneath it they found a ready-made tunnel – quite a short one, probably dug by a beetle or a mouse, ending in a little round nest-cave. It was quite dry there, though they could hear and smell the rain soaking the earth. With centipedish sighs of relief, they rubbed the wet off their cuticles and curled up together.

While they were asleep the rain stopped – for the moment. That’s how the rains are, in the tropics. They start – they stop – and then, when they start again, that’s it – it rains for months. But the centis didn’t know that. The drumming sound stopped, and it was peaceful and still. And then – George suddenly woke up. He reared up and bumped his head.

“Hx! Wake up! What’s that?”

Harry woke up and listened, or rather, felt. There were strange vibrations. It wasn’t the rain falling. And it wasn’t just one creature walking, slithering, hopping or crawling on the no-top-world. It sounded like masses of tiny things. So many that the vibrations covered a huge area.

“Is it the marine centipedes? Are they after us?”

They were coming closer, whatever they were. Soon they would be right over where the centis huddled in their earthy lair.

“Quick, Hx! We’d better block the mouth of the tunnel!”

They started toward the entrance. But it was too late. The invaders were already there.

They marched in file, two at a time, down the tunnel. Harry and George stopped short, frozen with fear.

It was the most dreaded thing in the world.

Soldier ants!

Soldier ants are absolutely terrible. Even Hoo-Mins are afraid of them and so is every other creature in the tropics. They can bite and sting, and every now and then they leave their nests, millions of them, and march through the forest, overpowering, killing and eating every living thing in their path. Nothing can stop them except fire. And there was no fire here.

The ants were on the march.

Belinda had warned the centis about them many times. She told them: “If you sense them coming, run. Get out of their way. Or go deep underground, though they may follow you. If they corner you, there’s nothing for it but to fight as long as you can.”

Harry and George turned tail and fled, but there was nowhere to flee to. As they came up against the back wall of the nest, they had to stop because there was no time to dig any deeper. They turned again. They were trapped. The soldier ants were coming. The leaders were halfway down their short tunnel.

Harry was perfectly sure they were done for. But he said, “We must fight! Don’t

let them come into the cave. Let’s block the tunnel!”

They had only a few seconds. They began frantically throwing earth to form a wall at the nest-end of the tunnel. When they’d partly blocked it, only one ant at a time could crawl over it.

The centis prepared for their last fight.

As the first soldier ant poked its feelers and then its head over the barrier of earth, George lunged at it. He was shocked by the size of its head. It was far bigger than an ordinary ant, and this was due to its huge, ugly jaws, which were open to bite. But George got in first, and snapped its head off with his poison-pincers. Harry did the same with the next one.

The bodies helped block the tunnel. But others were behind them. They swiftly carried the bodies back along the tunnel, passing them from ant to ant, while other ants tried to get into the cave.

As fast as Harry and George dealt with them, so the bodies were cleared and more ants poured down. The centis knew even though the ants were small they could do what the marine centipedes had done – overwhelm them with numbers. They would just smother the centis’ breathing-holes and then bite them to death.

The vibrations overhead were now shaking the earth. These were not the soldier ants. They were driver ants – the main body of the ant army. The soldier ants were their guards. They marched in thick lines alongside the phalanx of marching drivers. The coming of the rains had triggered them to start marching through the forest, looking for food and a new nest-site.

You might not feel the shaking caused by so many million tiny feet, but to the centis it sounded as a machine-drill would to you. The vast army of ants were passing over the top of the centis’ nest-cave in their countless millions. Every ant the centis killed, they knew could be replaced by scores of others.

It was hopeless. All was lost!

But they battled bravely on. They had no hope, but they were not going to give up easily.

As they fought frenziedly, killing ant after ant, something changed. The drumming vibrations over their heads got less and then petered out altogether.

As if at a signal, the invading soldier ants turned away.

Their marching column had gone past. Those attacking the centis had to go, too. Suddenly, there were no more ants. No bodies even. They had all gone, as if they had never been there.

The two exhausted centis stretched out side by side. They’d got a few stings but nothing much. The worst thing was the awfulness of having been so afraid. It took them a long time to get over that. And of course they were dreadfully tired from the battle.

They managed to stagger up and block the tunnel entrance and then they fell into a deep sleep until evening.

17. An Old Enemy

When night came, they woke up.

They were desperately hungry.

“Those foul soldier ants might have left us just one or two of their stopped ones to eat,” complained George. “We earned them!” They pushed their way through the earth block and tested the night air with their feelers. They could smell the hated smell of the driver-ants’ column from all the droppings they’d left. They saw how everything that had been in their path had been eaten.

“Nothing left for us, not even a head,” said Harry gloomily. “Oh well. We’d better get on our way.”

“Can you still sense the no-end-puddle, behind us?” asked George.

“No. It’s too far away.”

“How are we going to keep going in a straight line?”

“Is home even in a straight line? The giant flying-swooper could have flown crooked.”

“We’ll never find it.”

But now it was Harry who kept George’s hopes up.

“Yes, we will. I know we will. There are other things that roam, besides the driver ants. Things that don’t have homes like we do, they travel around. Maybe they’ve seen Mama. She must be looking for us.”

So they started forward again.

It’s very hard, when you’re small and close to the ground, to know which way you’re going. Even Hoo-Mins can walk around in circles when they don’t know their way, and they’ve got the sun to help them, and maps, and landmarks, and they have binoculars to see far away. The centis just had to keep on plodding along through the underbrush, over and under everything that was in their way, hoping for the best.

But then they had a bit of luck. Not that it looked like luck when they first saw it – quite the opposite!

They heard it coming, and dived under some dry leaves to hide. It was a single thing, this time, not hoards of ants on the march. They heard it tiptoeing here and there, hardly causing any vibrations, but making a very faint rustling. It sounded as if it, too, might be lost.

Harry peeped out from under a dried palm frond. The tree it came from was nearby and he was ready to run up it if danger threatened. And it did! Because he could see the thing now. It would scuttle a little way. Then stop and wave its feelers about. Then scurry a little nearer. It looked fearsome – large, and hairy, and stripy, and horrible.

“It’s a tarantula!” crackled Harry into George’s ear-hole. “Up the tree – quick!”

They came out from under the dry stuff and rushed up the tree. Some palm trees, if you’ve noticed, have sticking-out bits on their trunks. They were like little balconies, to the centis. As they climbed, Harry had an idea.

“If we climb right to the top,” he said, “we might be able to see something.”

“Like what – a hole in the ground?”

“Don’t be so smart. No. Like the Hoo-Mins’ nest where we were caught. If we could find that, we could get home easily.”

Of course the centis had no idea about houses, but they knew that the place they’d been shut up in stood up from the ground quite a long way. Harry had even caught a glimpse of it as the Not-So-Big Hoo-Min had prepared to throw them up into the tree.

So they climbed nearly to the top of the palm tree. They lay out along two of the sticking-out bits on the trunk.

The tree was taller than most of the others. The house they were looking for was actually in plain sight, not very far away. But of course the centis, with their weak little eye-clusters, couldn’t make it out.

“I wish we were friends with a flying-swooper,” said George, peering about uselessly, “like Danny said he was.”

“That was a not-so,” said Harry. “No centipedes could be friends with a flying-swooper. He was just trying to scare us.”

Just then they heard something coming up the tree after them.

They instantly reared up their first eight segments to be on guard, and looked straight down.

Climbing slowly and carefully up the tree was the tarantula.

Harry had learnt some Tarantulian – well, some tarantula signals, anyway when they’d all been in their hard-air prisons together. Now he sent an unmistakable Tarantulian signal.

“Stop right there if you know what’s good for you!”

The tarantula stopped, crouching just below them. They were in the best position. They could easily have rushed down and attacked her from each side. She looked up at them with her wicked little eyes.

Suddenly George nudged Harry.

“Hey! That’s our tarantula!”

“It can’t be!”

“It is!”

They dropped on to all forty-two legs and peered down at the great spider. She peered up at them. Slowly and carefully, she sent a signal.

“I’m not hunting.”

They relaxed. That signal was something everyone understood. It was like pax with us – they knew they were quite safe.

They both signalled back: “We’re not hunting.” She looked relieved. She was gripping on tight with her feet. Climbing trees was not her best thing.

“Come here. Help,” Harry signalled.

Help? Help a centipede? Puzzled but curious, the tarantula climbed up to them. She looked suspicious, even though they had promised not to harm her.

“You see Hoo-Min nest?” asked Harry.

He had to ask se

veral times before she understood. At last, though, she grasped what they wanted.

“No see. But know.”

“You know – where we were – caught?”

She signalled yes.

“You – show – us?”

She looked at them blankly. Even from that look, they took a clear signal. “Why should I? What are you to me but enemies and food?”

Then they knew that she had followed them up the tree to catch them, and had changed her mind only because she realised she couldn’t hope to win against both of them. As Belinda was forever saying, quoting from Beetle: “If you hunt two, they’ll hunt you.”

Harry felt himself getting mad. This great ugly greedy creature knew where his home was. She could take them there – it couldn’t be far or she couldn’t have got here. He remembered her in the hard-air, glaring around, sending threatening signals about gobbling them all up.

He rose up high on his last four segments. “You show or we attack!” he signalled fiercely.

The tarantula gave a jump of fright. George got quickly in front of Harry.

“Hx! You can’t break the rule!” he crackled. Harry sank back, trying to get hold of himself. Once a creature says “I’m not hunting,” he can’t go back on it without first giving clear warning that now he is hunting. It’s one of the first rules among hunters.

George was not much good at other creatures’ signals. He said to Harry, “Tell her she ought to help us because we were caught together.”

“That’s too hard, I can’t signal that!” said Harry. “Anyway, she wouldn’t, she’s horrible.”

While they were arguing, the tarantula seized her chance, turned, and fled down the tree as fast as she could, zigzagging among the sticking-out bits.

Seeing she had a good sporting lead, Harry signalled after her: “We’re hunting!” He wasn’t sure if she’d got it, but anyway now the peace was broken. The two centis shot down the tree after her.

When they reached the ground they saw her making off at speed between the roots and rotting stuff on the ground, almost dancing along. She couldn’t run as fast as they could.

Two Is Lonely

Two Is Lonely Uprooted - a Canadian War Story

Uprooted - a Canadian War Story The Backward Shadow

The Backward Shadow Harry the Poisonous Centipede: A Story to Make You Squirm

Harry the Poisonous Centipede: A Story to Make You Squirm The Secret of the Indian (The Indian in the Cupboard)

The Secret of the Indian (The Indian in the Cupboard) The L-Shaped Room

The L-Shaped Room The Mystery of the Cupboard

The Mystery of the Cupboard The Farthest-Away Mountain

The Farthest-Away Mountain Harry the Poisonous Centipede Goes to Sea

Harry the Poisonous Centipede Goes to Sea The Fairy Rebel

The Fairy Rebel Harry the Poisonous Centipede's Big Adventure: Another Story to Make You Squirm

Harry the Poisonous Centipede's Big Adventure: Another Story to Make You Squirm The Indian in the Cupboard

The Indian in the Cupboard The Return of the Indian

The Return of the Indian I, Houdini

I, Houdini The Key to the Indian

The Key to the Indian The Warning Bell

The Warning Bell Alice by Accident

Alice by Accident Uprooted

Uprooted Writing On the Wall

Writing On the Wall The Adventures of King Midas (Red Storybook)

The Adventures of King Midas (Red Storybook) Harry the Poisonous Centipede's Big Adventure

Harry the Poisonous Centipede's Big Adventure Harry the Poisonous Centipede

Harry the Poisonous Centipede The Dungeon

The Dungeon Bad Cat, Good Cat

Bad Cat, Good Cat The Indian in the Cupboard (Essential Modern Classics, Book 1)

The Indian in the Cupboard (Essential Modern Classics, Book 1) Tiger, Tiger

Tiger, Tiger